Russians pronounce my name ‘Torm’ in a way which I have always found quite delightful. This fact didn’t, however, stop me from feeling a bit nervous before opening the door.

I entered the room clutching the bottle of malt. I entered a hubbub of drinking and toasts and men.

There must have been 10 or 12 middle aged male artists packed into the room sitting on assorted chairs all holding small vodka glasses. A bottle was going round filling up for the next in what had obviously already been a long series of toasts.

Sasha the sculptor spots me and starts to shout ‘Torm’ and comes over and gives me hugs that could crush a bear and huge slurping kisses on my cheeks.

I don’t catch the fast slurred Russian he is saying. Rapidly I am handed the first in a succession of extra large vodkas which I down.

I had been studying Russian on the tube so I tried a bit. “kak dyela sasha ochin preatna’.

“Oah Torm maladyets ti uchil pa roosky harashoa” cried Sasha.

I felt myself entering that altered state you adopt when you are surrounded by people speaking a language you barely understand. You get used to not knowing much of what is going on and you let the ‘not-knowing’ wash over you. You try to build some coherence out of the odd words you think you understand and other cues like body language.

This takes a certain amount of concentration so if you are tired or drunk often you just give up and feel really isolated and reality becomes a jigsaw with mo pieces missing. As this feeling descends I wonder if it is what it is like being a baby or having Azheimer’s.

And then I wonder if babies or dementing people wonder things like that.

Sasha talked very fast to his visitors. When they speak russian I hear ” blah blah blah blah TORM blah blah SCOTLAND blah blah blah blah GOOD”.

I produced the bottle of malt and tried to make a plea for savouring the taste. When I speak, instead of my experience of listening to their Russian , that of catching the odd word within a stream of unintelligible Russian sounds, they just get the odd Russian word punctuated with ‘ers’ and ‘ums’.

“Not vodka. Er. Not …fast. Um…Whisky good. Slow” I said trying to pronounce the words as if spoken by the female voice in my headphones on the Central Line.

I guess it was like a man with bad english saying the word Coffee followed by another word that could be biscuit or basket and manchester. The room listened respectfully but looked entirely unburdened by understanding. I wasn’t even sure if they knew I was trying to speak Russian.

I turned to the other Sasha (the photographer who spoke some english) and asked him in English to explain that whisky is meant to be drunk slowly in order to experience the complex taste and that I had bought Sasha the Sculptor one of the best whiskies to say thanks for taking me hunting, so they should really take extra time to savour this and request they don’t down it one like vodka.

Sasha the photographer, in his earnest hangdog style, explained my request at length to the group who proceeded to pour out the whisky in to the vodka glasses thus using up the entire bottle of very expensive malt giving each person a tiny dribble.

Bam! They all downed it in one gulp and then gave each other quizzical looks while nodding and looking at their empty glasses. We had achieved one of the lowest Effort Expended vs Flavour Experienced ratios in history.

I didn’t know the Russian for tumbleweed.

It was minus 20 outside. I had been in Rostov for four hours, in Sasha’s studio for 15 minutes, I was already pretty pissed and had no idea that the craziness had only just begun. Welcome to Russia.

I visited Rostov on Don in the very south of Russia for the first time in 1990. We went initially as part of a celebration of Rostov’s twin town status with the Socialist Republic of Glasgow. At that time Perestroika was in it’s early stages and it was still uncommon for westerners to go there.

We were told that we were the first western jazz group to visit Rostov since Duke Ellington went there in 1972* and we were treated with a lot of respect and warmth.

The full story of the first trip will need to be told on another occasion but nine months later I was back in Rostov for,wait for it, a third trip. Why? To visit Lina, the Russian girl I had fallen for. Not for the last time in my life I was being unrealistic.

On quite a large scale.

I was also there to spend two months working as a medical student.

As seemed common in Russia at that time many people were very friendly. In retrospect it was partly out of the natural hospitality of the russians and the curiosity of those cut off.

But also partly it was a kind of investment.

Russians were adept at building mutually beneficial friendships as a way of circumnavigating the intricacies and idiocies of communist bureaucracy. It was a big part of the way they survived the communist system, and there was a way they could be beautifully collective and cooperative.

They could see Russia was finally going to open up and recognized that having friends and connections in the West could really help them. As we were the first and only westerners they had met we must have seemed like gatekeepers to a promised new land. One big problem was that they didn’t really have a clue how the west operated and as a result they had no idea how powerless we were to help them.

One of these friendly investors was Sasha the tall and lovely photographer who adopted us from day one of our first trip and seemed to just always be there. Sometimes I wondered if he was KGB.

Incidentally he finally made his play by giving us a bunch of bizarrely translated handwritten letters to give to the head of Kodak to make a a bid to become the Russian distributor for Kodak.

Anyway during the first trip Sasha took George, the bass player, and I to meet his friends the sculptors one of whom, the big guy, was called Sasha as well.

The first visit consisted of getting absolutely fall down drunk in the morning while photographer Sasha translated for us. These guys had spent their entire lives building huge monolithic sculptures celebrating Soviet Russia, a regime which they passionately hated.

Now the Soviet edifice was collapsing they were happy but falling with it was the demand for their work and as a result their livelihoods. They hadn’t been paid for months.

Part of their anti-soviet stance was to eschew the expression ‘Comrade’ and to instead address their toasts to ‘Gaspada’ , which means ‘gentlemen, while drinking with their elbows held out horizontally to the side. This was the toasting style of the Cossack cavalry who had been crushed by the Red Army. You got the feeling that until fairly recently this was totally taboo behaviour.

While we there sculptor Sasha took a small bronze bust of Marx and put clay on it and made a pretty good wee sculpture of me as a gift which I took home for my mum.

On my first trip back to Rostov to see Lina photographer Sasha met me at the train station and informed me that sculptor Sasha wanted to take me hunting which he did and again is another story.

So it was on my second trip back that I had bought sculptor Sasha that bottle of very good malt whisky as a gift from Scotland. In the interim period he had moved his studio to some kind of artists colony where a whole team of artists, all seemingly of similar vintage, had places to work.

Sculptor Sasha also had some artists visiting from another town when we arrived to drop off the malt, so there was a crowd.

After the barely noticed demolition of the malt I was swept along in a series of toasts with a large vodka downed with each one. Unusually for russian drinking sessions there was no food so I was getting really hammered.

Suddenly this guy I didn’t know was beckoning me to follow him. I could see he was as drunk as we all were. He was speaking fast in Russian and was very insistent. I realized he wanted me to go upstairs so I followed him.

We entered a different studio lined with heavily coloured modern paintings in the Chagall, Miro, Kandinsky artistic ballpark. . He went round them giving me huge futile speeches on each one that I didnt understand at all. I wasn’t sure but the paintings didn’t look that great.

I listened intently and nodded. I had no idea what I was doing there, what he was saying, nor what he wanted from me. I begin to feel like I wanted to go home except I hadn’t established where my current home was. I guessed how drunk the guy must have been to assume I could understand Russian after the totally shit display I had put on tying to speak it.

Suddenly Sasha the photographer appeared in the drunk painter’s studio. “Thank god!” I thought “Rescue”.

“Tom please come quickly” Sasha looked more than normally hang dog. “My friend has fallen down, please come quick.” He knew I was a medical student because he helped arrange my student elective placement at the local special care baby unit where I was shortly to start work.

You know the sound they often use on Tv,of a needle being suddenly wrenched off a vinyl record this stopping the background music,to indicate an abrupt change of mood. Well that was the feeling. It is the trainee doctor’s worst nightmare, being asked to do something you’re not competent at whilst very pissed.

We went outside. It was dark and very cold, the kind of cold that freezes the inside of your nostrils when you breathe in through your nose. There was a crowd of drunk artists under some street lights. One of them lay on the pavement with another one rubbing his chest in a circular motion. It wasn’t till days later that it occurred to me this may have been a totally misguided attempt at ‘cardiac massage’. The guy on the deck was a deep grey blue colour .

Something in me kicked into action and despite it being really bizarre having an audience of gawping pissed sculptors I started doing CPR. 15 cardiac compressions to every breath. I had no choice but to do straight mouth to mouth. As I put my mouth over the man’s lips I could smell the sickly sweet smell familiar to anyone who has ever kissed anyone who is extremely drunk, a mixture of cider, vinegar, nail varnish, a hint of vomit and cloves.

Many years later my GP neighbour Sharon told me that you could easily count to 15 by singing the chorus to Nellie the Elephant up to the first Trump, Trump, Trump but that would have been too surreal.

The man’s colour pinked up as I worked meaning I was getting oxygen in and around his body.

“Have you called an ambulance” I shouted in between breaths.”Da Da Da” came an unconvincing reply. The sculptors seemed to be really taken aback by what I was doing, as if it was some bizzare Scottish faith healing ritual.

After what seemed like forever doing CPR I kept shouting more and more insistently “where is the fucking ambulance ?”. I think I must have been going for 10 minutes or more. My arms and back started to really hurt with the effort and the cold. He was a big man and to get his chest compressed was like trying to close a large very overfilled suitcase.

Eventually I realized I needed an assistant. I beckoned a man to come over. The russian sculptors were milling around talking animatedly.

I gestured to him to kneel down and demonstrated how to interlace the fingers and to push down with straight arms on the heels of the palms over the mans lower sternum slightly to the right. I had no language to explain anything.

I went to give him a breath and at that moment my assistant gave a huge misguided push on the stricken mans stomach and my mouth filled with his stomach contents.

This was a pretty gross sensation but oddly familiar. Having your mouth fill with vomit and alcohol wasn’t totally unfamiliar to a rugby playing medical student – I guess it had just come in from a different direction.

By this time I was too far in to be grossed out or stop so I just spat out the vomit tried to communicate to my assistant a) push higher up and b) not when I am doing a breath.

We carried on. I had to spit out vomit once or twice more so I went back to doing it all myself. I kept shouting “where’s the bloody fucking ambulance”. It seemed to go on for ever.

Finally an ambulance draws to a stop near to us, no blue light, no siren, nothing.

A thin man with stubble smoking a cigarette and wearing a white coat slowly parked the ambulance, opened the door climbed out and carefully shut the door. He unhurriedly saunters over and leans over slightly to look at the guy on the floor from a couple of metres away. He removed his cigarette holding it between thumb an index finger like an OK sign.

There is a pause.

“He’s dead!” he pronounces. No checking pulse, no stethoscope, no torch in the pupils.

With that he replaces the cigarette, turns on his heel, walks back over and climbs back in the ambulance and drives off leaving the dead man on the pavement.

There is no time really for me to react to this sequence of events truly shocking to a British person because I am enveloped in a crowd of totally pissed cheering Russians who seem very impressed with my CPR efforts.

I am swept away back inside leaving the body alone lying in the snow on the pavement. Later I was told he was lying there for 6 hours.

The party far from being diminished by the tragic turn of events seem only to be intensifying. I am taken into another part of the building and the alcohol and the death has cranked up the energy to a kind of frenzy. Everyone seems to be talking all at the same time really excitedly Suddenly I am face to face with this new sculptor, an absolute bull of a man.

He isn’t a big man. Not tall but he has really big arms and shoulders, in the way a farmer or stonemason does, not a bodybuilder.

He is probably in his forties, wearing a white vest and cream trousers with a rope for a belt and had very short very black hair. He looks like a really hard fucker and he is squaring up to me but somehow not in an aggressive confrontational way.

It is almost like a welcome ritual. So I don’t feel threatened but I have no idea what the hell is going to happen.

He looks right into my eyes with his eyes blazing with ferocious intensity. Next he places his hands either side of my face and pushes his forehead hard against mine and squeezes and pushes really hard against my head as he let’s out what can only be described as a roar.

For some reason I feel like I know what to do – which is to return the push and roar back.

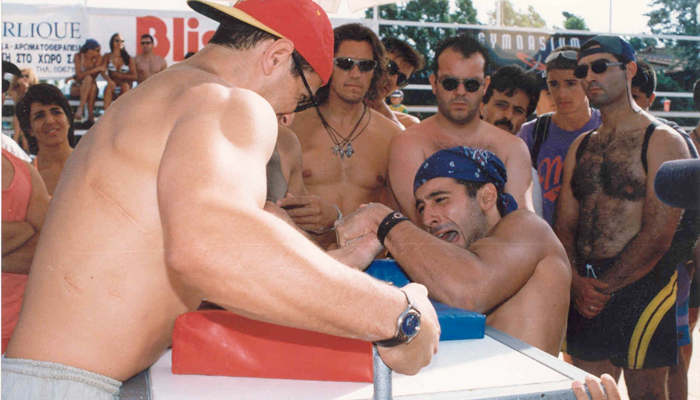

He seems pleased with that and we disengage. He barks some Russian at photographer Sasha. Sasha says “Victor wants to, how you say, … arm wrestle!”

The whole sequence of meeting Victor and the intensity of it all emotionally and physically, and the inability to understand the words being shouted throughout, now means that the whole scene with the ambulance driver and the dying man, even though it finished less than 10 minutes ago, seems like a kind of disjointed dream.

So within a few minutes I was in a really full on arm wrestle with this guy which somehow I managed to win – this only further intensified my status and the amount of alcohol I was being offered.

The rest of the night is a little hazy in my memory.

I do remember that a week or so later the dead man’s family wanted me to go to their village to meet them because they believed his spirit passed through me as he died.

* although that didn’t seem to merit a mention in the book on the history of jazz in Rostov that I saw when I returned 17 years later with the sax player Paul Towndrow – a trip that merits it’s own story or two.